The recitation of the Ten Plagues that assailed Egypt has stimulated the imagination of writers and readers throughout the ages. Not less found among them are the biblical authors and editors of the book of Exodus, who devoted seven chapters to this saga, in fact, the most extended single dramatic episode of the TaNaKh.

However, “the more one looks into,” comments David Gunn, a Bible scholar who has taught at the University of Sheffield in England and Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia, “the more muted the picture appears. The signs and wonders conceal destruction and suffering, deserved and undeserved- an excess of havoc.”

The liberating act is presented as violent. All of Egypt was made to suffer, with the plagues that extended over the whole land of Egypt forcefully also affecting the Israelites living there.

Because the significance of the plagues is theological, the natural question is: what does this tell about Israel’s God?

The late Yale University professor Brevard S. Childs directed us, for an answer, to look at other books from the collection called the TaNaKh, the Hebrew Scriptures.

The book of Deuteronomy (chapter 6, verse 22), for instance, says Professor Childs “did not bother to mention any of the ten plagues that are recounted in such detail and at such length in the Book of Exodus contenting itself with a passing reference to “signs and wonders, great and sore, upon Egypt.” The prophets passed over this tradition altogether.

In short, the picture that emanates from the TaNaKh itself is one of “toning down,” where the plague tradition was relegated to a minor role, sharply reworked, or directly ignored.

This form of necessary theological criticism within the TaNaKh itself developed so as not to contradict Israel’s true values.

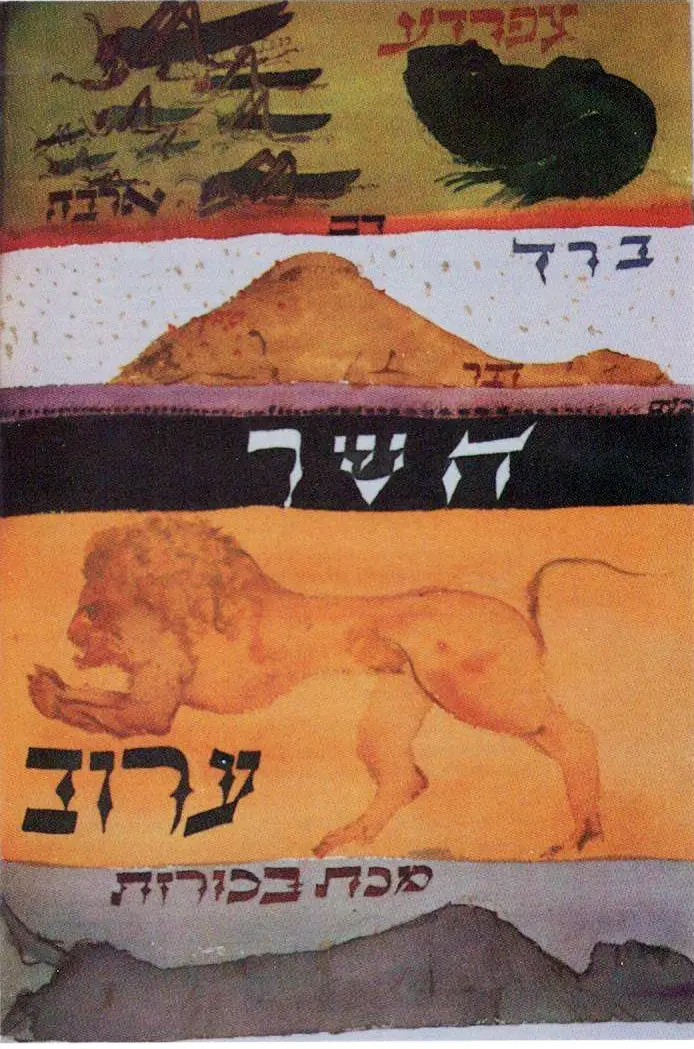

Understanding that the purpose of the plagues was not the physical harm of the Egyptians but rather a symbolic desecration of their many gods – blood desecrates the Nile, which was worshiped as a god, locusts desecrate the corn god, and so on- late generations of Biblical writers soft-pedaled the interpretative imagination of those preceding them.

Proof of this tendency is to be found in the Yalkut Shimoni, a 13th-century compilation of ancient rabbinic comments that states:

“Three references to rejoicing are found (in the Pentateuch) concerning the festival of Sukkoth. However, there is no such reference concerning Passover.

Why not?

Because that year’s season was a time of death for many Egyptians. (When Israel came out of Egyptian slavery, many Egyptians died during the plagues.)

Thus, indeed, is our practice: All seven days of Sukkot, we recite the prayer of Hallel (joyous praise of the Lord), but on Passover, we recite the prayer of Hallel in its entirety only on the first day.

Why? Because of the verses, ‘do not rejoice in the fall of your enemy, and let not your heart be glad when he stumbles’ (Prov. 24: 17).”

An essential and often overlooked detail in reading about the “Ten Plagues” in Egypt (Exodus 7: 8-10: 29) is that we learn about the events through constant introductions such as: “

And the Lord said unto Moses…” (Exodus 7: 1) “And Moses and Aaron did so; as the Lord commanded them, so did they.” (verse 6); “And Moses was eighty years old, and Aaron eighty- three years old, when they spoke unto Pharaoh” (verse 7); “And the Lord spoke unto Moses and unto Aaron, saying:” (verse 8); etc.

Obviously, somebody other than the actors in the events is reporting what happened.

Because at the time of the Egyptian Exodus, “neither the cultural nor the material conditions for writing were conducive to the development of a book culture,” the probability that these events were not reported at the time of their happening but very much later is very high. In any event, we have to contend with not so much about the event itself as with the writer’s perception or the communal remembrances of the event.

In other words, we read about the Ten Plagues through the understanding and interpretation of the “reporter.”

“The narrators who told the story of the liberation from Egypt in the epic style which we find in Exodus chapters 7 to 14 were dealing with historical events, but their method was very different from that of the chronicler or the modern scientific historian. These narrators painted their story with bold strokes to bring out the essential meaning of the events. They used hyperbole to bring out the important point the same way that we might use underlining or italics, says James Plastaras, who wrote a book called The God of Exodus: The Theology of the Exodus Narrative. In his A History of Judaism, Rabbi Daniel Jeremy Silver echoes: “The miraculous legends of the plagues which brought Egypt to its knees, […] of staves which turned to snakes, represent the inevitable literalization of radical amazement. How else does one shape the incredible into words?”

The biblical authors did not share with us our conception of autonomous laws of nature. All the Israelites knew was that God had done it. Plastaras keeps saying, “How he had done it was of secondary importance. Was there anything miraculous about the locust plague, or was it essentially like the other locust plagues that afflict the countries of the Near East from time to time? The ancient Israelites would have found it difficult to understand such a question. Every locust plague would have been, in his eyes, the work of God. He did not divide God’s works into the two categories: “within the order of nature and “outside the order of nature.”

Thus, the biblical narrative does not answer the modern question: natural or miraculous? It simply affirms that God did these things in order to free Israel. A number of the plagues seem to be related, in fact, to phenomena that are well-known in Egypt, though perhaps quite infrequent. The biblical narrative does not force us to conclude that the plagues were completely unheard-of phenomena.”

“All the elaborate speculation about the natural causes of the Ten Plagues and other biblical wonders,” writes Jonathan Kirsch, author of Moses: A Life, “misses the point that the biblical authors were trying to make in the first place. The miracles reported in the Bible were supposed to strike the reader as miraculous.

Even if some natural phenomena can be found at the heart of the Ten Plagues, the theology rather than the natural history of the plagues intrigued the biblical authors and inspired them to tell the tale of the plagues as they did.